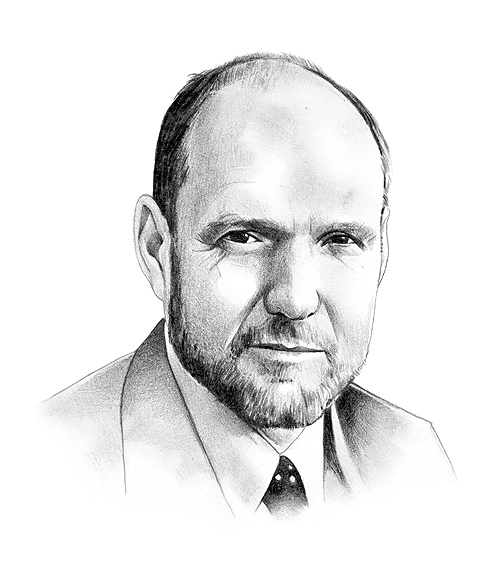

Richard Perle is a liar

- By Stephen M. WaltStephen M. Walt is the Robert and Renée Belfer professor of international relations at Harvard University.

-

I was thinking about two former American government employees this

weekend, and how the differences between them tell us a lot about why

the United States is in so much trouble today.

The first person is Eugene Kranz, the legendary NASA flight director immortalized in the film Apollo 13.

I watched a rerun of the film on Friday night, and was struck again by

his remarkable leadership of the team that improvised the astronauts’

rescue after an in-flight explosion crippled their spacecraft and placed

their lives in peril. Many readers probably remember the moment in the

film when Kranz tells his colleagues: “Failure is not an option.” This

line may have been apocryphal, but when I survey the landscape of

problems we face at home and abroad, I wish we had more people like

Kranz in key leadership positions.

China Quietly Abandoning Bid for ‘New Model of Great Power…

Beijing long sought a rhetorical reboot in bilateral ties. Now it’s talking differently.

Yes I know, it’s just a movie, but Ed Harris’s portrayal is consistent with what we know about Kranz himself. Above all, Kranz was a leader who took full responsibility for his actions. Here’s what he told his colleagues after the tragic fire on the launching pad of Apollo 1, a fire that killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee:

Spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity, and neglect. Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up. It could have been in design, build, or test. Whatever it was, we should have caught it. We were too gung ho about the schedule and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work. Every element of the program was in trouble and so were we… Not one of us stood up and said, ‘Dammit, stop!’…We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job. … From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: ‘Tough’ and ‘Competent.’ Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do…Competent means we will never take anything for granted…When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write ‘Tough and Competent’ on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.”

That is the kind of attitude that lands men on the moon, builds a healthy economy, and when necessary, wins wars.

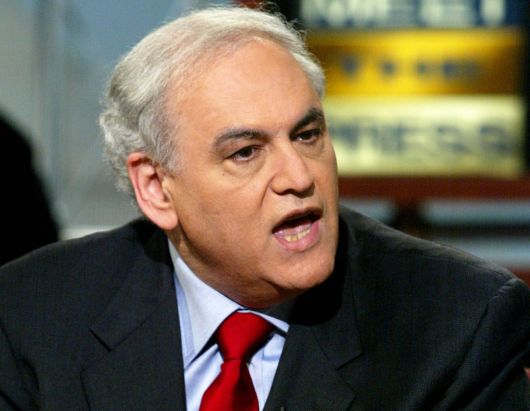

Now compare that frank and honest statement with the behavior of another former government employee: Richard Perle. In a recent article in The National Interest and a public appearance at the Nixon Center, Perle has tried to sell the story that neither he nor his fellow neoconservatives had any significant influence on the foreign policy of the Bush administration, and especially the decision to invade Iraq. Specifically, he denounces the supposedly “false claim that the decision to remove Saddam, and Bush policies generally, were made or significantly influenced by a few neoconservative ‘ideologues.'” He suggests that no one has ever documented this claim, either conveniently ignoring the many books and articles that did exactly that, or misrepresenting what these works actually say.

Given that Iraq turned into a debacle that the United States is having trouble escaping, it is hardly surprising that Perle is denying his role now. But that’s not what he said back when the war looked more promising. In an interview with journalist George Packer, recounted in the latter’s book The Assassins’ Gate, Perle described the key role that the neoconservatives played in making the Iraq War happen.

If Bush had staffed his administration with a group of people selected by Brent Scowcroft and Jim Baker, which might well have happened, then it could have been different, because they would not have carried into the ideas that the people who wound up in important positions brought to it.”

The “people who wound up in important positions” were key neoconservatives like Douglas Feith, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Paul Wolfowitz, and others, who had been openly calling for regime change in Iraq since the late 1990s and who used their positions in the Bush administration to make the case for war after 9/11, aided by a chorus of sympathetic pundits at places like the American Enterprise Institute, and the Weekly Standard. The neocons were hardly some secret cabal or conspiracy, as they were making their case loudly and in public, and no serious scholar claims that they “bamboozled” Bush and Cheney into a war. Rather, numerous accounts have documented that they had been openly pushing for war since 1998 and they continued to do so after 9/11. As neoconservative pundit Robert Kagan later admitted, he and his fellow neoconservatives were successful in part because they had a “ready-made approach to the world” that seemed to provide an answer to the challenges the U.S. faced after 9/11.

The bottom line is simple: Richard Perle is lying. What is disturbing about this case is is not that a former official is trying to falsify the record in such a brazen fashion; Perle is hardly the first policymaker to kick up dust about his record and he certainly won’t be the last. The real cause for concern is that there are hardly any consequences for the critical role that Perle and the neoconservatives played for their pivotal role in causing one of the great foreign policy disasters in American history. If somebody can help engineer a foolish war and remain a respected Washington insider — as is the case with Perle — what harm is likely to befall them if they lie about it later?

Let’s keep a few facts in mind. Perle and his neoconservative buddies helped develop and sell a policy that has left over 4,000 U.S. soldiers dead and more than 30,000 wounded, was directly responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Iraqis, and will end up costing the United States more than a trillion dollars. Yet instead of having the integrity and courage to acknowlege his role and admit his mistakes — as an honest man like Gene Kranz would — Perle now offers us a squid’s ink cloud of lies and prevarications. Although his absurd claims have been promptly and properly challenged, does anyone seriously think he will pay a larger price? The National Interest was all-too-willing to publish his rewriting of the historical record, and no doubt prestigious organizations like the Council on Foreign Relations will be happy to give him a platform at future meetings. Look for him on the Lehrer Newshour and CNN too; heck, he could even end up with his own show on Fox News.

Let’s face it: there is little or no accountability in Washington, where being wrong means never having to say you’re sorry; indeed, you don’t even have to admit responsibility for past mistakes, no matter how serious. It’s just the American taxpayer who ends up footing the bill, along with the soldiers who fought and died for these blunders.

As Frank Rich and others have figured out, we are in trouble today because we have allowed a culture of corruption and dishonesty to permeate our institutions and pollute our public discourse. Until that changes — until our public institutions contain a lot more truth-tellers like Gene Kranz and fewer liars like Richard Perle — we are not going to know where we stand, where we are headed, or whom to trust.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Like this article? Read an unlimited amount of articles when you Subcribe to FP Premium now 20% off.